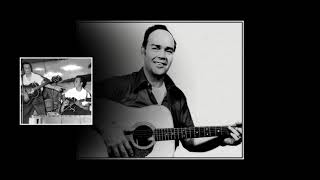

Earls was born on August 23, 1932, in Woodbury, TN. One of seven children, he spent most of his childhood living on a farm in Manchester. He developed a taste for country music and a desire to make his own music, listening to the two owners of the farm play their instruments and sing. Already encouraged by his mother to sing, at 16 he also took up the guitar and by 17 he was living in Memphis. As early as 1949, he formed his first band, but pursuing music full-time had to wait behind other of life's considerations -- he was married in 1950 and by the mid-'50s already had a growing family to feed. Still, he loved country music and thought he could make a living at it and in 1954, Earls formed a group that included Johnny Black, brother of music legend Bill Black, on guitar. This was a country band that played local bars and roadhouses, doing hillbilly music, one of hundreds in the Memphis area. The band's decision to spend ten dollars to cut a demo at Sam Phillips' Memphis Recording Services during the summer of 1955 put Earls into Phillips' orbit -- the producer liked the song, an original by Earls called A Fool For Lovin' You, and enjoyed Earls' singing, but told him he'd need a new band if they were to record anything.

Earls and Johnny Black stayed together, Black switching from guitar to upright bass, while Warren Gregory joined on lead guitar and Danny Wahlquist came in on drums. Their first recording session yielded a finished version of Lovin' You but also introduced a new original, called Hey Jim, that Phillips liked even better for the A-side. Then Earls brought in yet another original song that Phillips liked even better than Hey Jim for his debut. Slow Down reportedly had the legendary producer jumping up and down with excitement when it was cut at Sun, and it became the A-side even though Phillips had already renamed Earls' band the Jimbos to capitalize on the expected popularity of Hey Jim. Slow Down sold somewhere between 40,000 and 50,000 copies without ever charting, getting enough exposure in and around Memphis to perform respectably as a local and regional release. It might've done better but for the fact that Earls, who held down a job at a bakery to feed his family, couldn't really tour and stuck to playing venues close to Memphis. Slow Down elicited interest from DJs from as far away as Texas, who played the record on their air and would happily have put Earls the Jimbos on live, had they made the trip to the Lone Star State.

The $2,500 that Earls received for the sales that Slow Down did enjoy would have to suffice in lieu of a recording career, especially when Phillips declined to issue any further records -- he was around the studio enough, including the date when Elvis was trying to cut Mystery Train, and he cut enough sides to make a full LP, but Sun never issued any of them, possibly a result of Phillips' awareness that Earls couldn't do much to support their release with more than a few local gigs. It would have taken a truly exceptional record to overcome that handicap and Phillips evidently just never heard it in any of the sides that the man cut. Listening to those sides 40-plus years later, one's jaw drops at the stuff that was left on the shelf. Loose, hot rocking versions of Crawdad Hole that ought to have had teenagers bouncing off the walls and slow romantic laments like If You Don't Mind that were perfect for slow dancing and would've won over country listeners as well; ballads such as A Fool for Lovin' You, frenetic rhythm numbers like Let's Bop that...well, the title tells it; and Warren Gregory's lead guitar underlines the key points with the kind of dexterity you usually got from the likes of Karl Farr, exceeded only by Earls' frantic vocal vamping. Sign on the Dotted Line, a slow, burning country rocker sounds like Gene Vincent on a trip through rural Tennessee; When I Dream, a slowie with elegant guitar and drum accompiment that could've been part of Elvis' repertory and ought to have gotten a try from Tony Bennett or maybe Bobby Darin; the ominous, raw Take Me to That Place, based on Earls' observation of the inmates at an institution for the insane he used to drive by in his truck while making deliveries, that ought to have found its way into the repertory of the Stray Cats 30 years later. And finally, the minimalist My Gal Mary Ann, where the hottest guitar and drum work is all muted behind Earls' frantic, powerful countrified tenor, sounding like Carl Perkins with some loco-weed in his feed. They were all originals and one would've thought the publishing alone might amount to something serious for all concerned -- the man was a natural musician and songwriter and deserved a lot more recognition than he got.

By January of 1957, Earls' contract with Sun was over and so was his recording career, despite offers from Meteor Records and King Records. He kept performing as his time and energy allowed until 1963, when he moved to Detroit. For the next few decades, he made his living exclusively on an assembly line at Chrysler, raising his family and living the life of a responsible middle-class citizen, while Elvis Presley's star rose, fell, and rose again, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins got in and out of dire straits, and Johnny Cash became the musical conscience of the working man. He made a few attempts at recording in the 1970s, resulting in singles of Take Me to That Place b/w Mississippi Man, She Sure Can Rock Me b/w Crawdad Hole, and Flip Flop and Fly b/w Rock Bop.

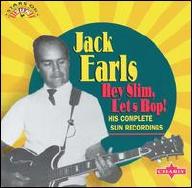

Finally, in the 1990s, after 40 years of pursuing music in his spare time, Earls began to realize some of the glory that might've been due him. The burgeoning interest in American rock roll and rockabilly music in Europe in general and England in particular drew Earls over to Great Britain, where he was greeted like a superstar. His Sun sides were compiled, first on LP by Bear Family Records and later in the 1990s on a CD from Charly Records entitled Hey Slim, Let's Bop, which is only slightly less essential listening than Elvis Presley's Sun recordings. In the years since, Jack Earls has played concerts in America as well played Las Vegas in tandem with Janis Martin and other survivors from rockabilly's first generation. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi