Following the end of the Second World War, he came to New York City, reunited with his family, and tried to enroll in the Juilliard School of Music, but found himself rejected over his never having earned a diploma from a high school. And so he headed west, to join one of his older siblings, and attended night school to formalize his education. He also enrolled in the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music, and earned something of a living working as an accompanist. He took what jobs there were in the early '50s, in whatever musical genres were required, and later moved back to New York, where he secured a job with producer David Merrick as the music director for the play +The Entertainer. With that credit under his belt, other doors opened, and he subsequently went to work for Vanguard Records, an independent label with an eclectic roster that encompassed classical, popular, and folk recordings, arranging albums of Greek, French, and Israeli folk songs.

While at Vanguard, he met Jean-Jacques Perrey, the French-born exponent of the electronic instrument the Ondioline, and seeing that they had a common interest in experimentation, the two decided to collaborate on recordings built from edited and manipulated prerecorded tape. Kingsley brought a sample of their work to Vanguard, which offered to release a full LP of their work, titled The In Sound from Way Out! (1966). The record sold well enough, if not spectacularly. but it opened up whole new commercial vistas for both musicians, mostly in the field of advertising at first. Ad agencies were always looking for quirky yet accessible sounds, and the album certainly showed those off. Equally to the point was Kingsley's special interest, manifested here and elsewhere in his work that followed, on humor in music. A string of commercials followed for various products, which established him within that industry in the mid- to late '60s. Starting with various blips, bleeps, and electronic squawks integrated into commercials, Perrey-Kingsley's work grew into jingles that included award-winning pieces such as The Savers, used for No-Cal soda. And Disney, no less, used their work as part of the nightly Main Street Electrical Parade at both Disneyland and Walt Disney World.

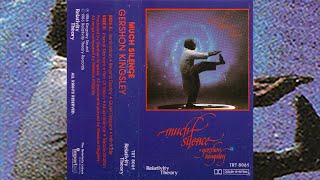

It was Perrey who knew Robert Moog, the musician/inventor whose synthesizer -- which in those days didn't resemble any kind of musical instrument that most people, or even most musicians, would recognize -- had just become available to the public. The Kingsley bought one of them, and the duo's second album, Kaleidoscopic Vibrations, incorporated it along with Perrey's Ondioline (and, indeed, was subtitled "Spotlight on the Moog"). Kingsley kept working with the new instrument, cutting a pair of LPs on his own for Audio Fidelity. One of his albums, Music to Moog By, was regarded as a breakthrough by electronic music enthusiasts, mixing these new sounds with the work of the Beatles, Simon Garfunkel, and Beethoven. At just about the same time, Walter Carlos, a Columbia University-trained electronic music specialist, released an album through Columbia Records called Switched-On Bach, which proceeded to break all sales records for what was officially a classical release. Although he had little enthusiasm for ventures such as that, preferring to break new ground with the new instrument, Kingsley was prevailed upon to try something similar, in conjunction with classical pianist Leonid Hambro, on the Avco Embassy label, and the result was the delightful Gershwin Alive Well Underground, devoted to George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue played on synthesizer and piano, and a brace of other Gershwin tunes (mostly from +Porgy Bess) played on the Moog. The album was immensely popular among musicians, and was a staple of programming on New York's WNEW-FM, among other free-form stations, for years to come.

It was around this time that he came to the attention of impresario Sol Hurok, who was sufficiently intrigued to put Kingsley at the front of a Moog quartet that performed at Carnegie Hall in 1970. The result of that endeavor was the First Moog Quartet, and a Carnegie Hall debut for the group and Kingsley. The critics mostly didn't like what they heard, but Arthur Fiedler, the director of the Boston Pops Orchestra -- who, a generation earlier, had turned an obscure piece of Baroque music by Johann Pachelbel, called Canon in D, into a hit -- did like it, and commissioned a Concerto for Moog, which the First Moog Quartet performed with the Boston Pops Orchestra the following year. The group toured the country, and it was in the course of his work with and around the quartet that Kingsley wrote a jocular little instrumental that seemed to go over as well as anything else in their programs. When he played it for the group (at a recording session in L.A.), he asked the musicians what they thought it should be called. One musician said, "Popcorn. But not what you think-- 'Pop' is for 'popular music' and 'corn' for 'corny'." That piece, recorded by quartet member Stan Free (with Kingsley) under the alias Hot Butter, became a monster hit in 1972 all over the world.

Kingsley was never able to achieve such success again as a popular composer, but in the years that followed kept experimenting with the Moog and writing new material, and went into film music as well (where his electronic sounds were mostly favored for horror and science fiction vehicles, most notably Disney's #Tron). In 1969, amid all of his burgeoning recording and composing activities, Kingsley also found the time to write Shabbat for Today, God, and Abraham, which has been acknowledged as the first rock-inspired piece of sacred music ever to be performed in a synagogue. This work pointed to the other major thread of Kingsley's career, his explorations and resurrections of Jewish music and Yiddish culture. His work and compositional voice in this context has been, at the very least, unique, and the mix of these various threads of his career has made Kingsley a singular figure in music for 40 years and counting, as of 2009. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi