Born David Harrison Macon in Smartt Station in middle Tennessee's Warren County, he was the son of a Confederate officer who owned a large farm. Macon heard the folk music of the area when he was young, but he was also a product of the urban South: after the family moved to Nashville and began operating a hotel, Macon hobnobbed with traveling vaudeville musicians who performed there. After his father was stabbed near the hotel, Macon left Nashville with the rest of his family. He worked on a farm and later operated a wagon freight line, performing music only at local parties and dances.

Macon's turn toward a musical second career was due partly to the advent of motorized trucks, for his wagon line fell on hard times in the early '20s after a competitor invested in the horseless novelties. In 1923, he struck up a few tunes in a Nashville barbershop with fiddler Sid Harkreader, and an agent from the Loew's theater chain happened to stop in. Soon Macon and Harkreader were touring as far a field as New England, and when George D. Hay began bringing together performers two years later for what would become the Opry, Macon was a natural choice. The tour also brought Macon the first of his many recording dates, held in New York for the Vocalion label in 1924. Macon would record prolifically through the 1930s (and occasionally up to 1950) for various labels, accompanied at different times by Harkreader, the brother duo of Sam Kirk McGee, the Delmore Brothers, the young Roy Acuff, and other string players including a then-unknown Bill Monroe. For secular material, his backing band took the name of the Fruit Jar Drinkers.

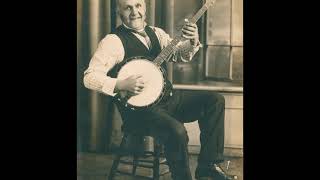

Macon's recordings are richly enjoyable in themselves and are priceless historical documents, both for the large variety of banjo styles they preserve and for the window they afford on American song of the late 19th century. Macon performed musical-comic routines such as the "Uncle Dave's Travels" series, topical songs, often of his own composition (Governor Al Smith), playful folk songs (I'll Tickle Nancy), gospel with his Dixie Sacred Singers, blackface minstrel songs, unique proto-blues pieces that Macon learned from African-American freight workers (Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy), and songs of other types. Yet "the Dixie Dewdrop" was loved most of all for his presence as a live musician, captured not only on the weekly Opry broadcasts (which were broadcast nationally for a time in the 1930s) but also in the 1940 film #Grand Ole Opry. Macon delivered what an 1880s southern vaudeville audience would have demanded for its hard-earned dollar: showmanship (he handled the banjo with Harlem Globetrotters-like trick dexterity), humor, political commentary (often of the incorrect variety by modern standards), and unflagging energy.

Macon continued to appear on the Opry almost until his death, gradually taking on the status of a great-hearted living link to country music's origins. He became the tenth member of the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1966, and the revival of old time music that flourished as part of the folk movement focused the attention of younger listeners on his music. Yet Macon remains less well understood, and less present in the musical minds of country listeners, than Jimmie Rodgers or the Carter Family, even though he was nearly as well-known in his own day. Perhaps that's because he represents an older layer of American music-making than almost any other performer known to country audiences: modern hearers can easily connect with Rodgers' blues or the Carters' homespun sentiment, but Macon may require greater effort. Such effort, in any case, is well repaid by an acquaintance with his musical legacy. ~ James Manheim, Rovi