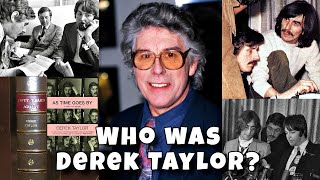

That glowing review helped him get access to the Beatles for a number of stories over the following year. This was a time in which the boundaries between maintaining an objective reporting stance and profiting by association were less important among music journalists than today. So it was that Taylor ended up ghostwriting a weekly column by George Harrison for The Daily Express, and then ghosting Brian Epstein's autobiography. Indeed, Taylor impressed Epstein and the Beatles enough to be hired as Epstein's personal assistant and the Beatles' press officer in April 1964. Although Taylor worked in this capacity for a while, he quit after a row with Epstein, although he remained friends with the Beatles and their manager. Taylor then moved to Hollywood and became, probably, the most famous rock publicist of the mid-'60s, working with the Byrds, the Beach Boys, Paul Revere, and less commercial artists such as Captain Beefheart and Phil Ochs. He also helped bring Harry Nilsson to the attention of the Beatles, who became fans of his, with John Lennon becoming a close friend of Nilsson through the mid-'70s.

Reading Taylor's press releases and hearing about his publicity campaigns today, his prose and efforts on his clients' behalf may seem gimmicky, naïve, overly sunny, or superficial. In the context of the times, however, he was an important liaison between the groups and the straight business world. He was not afraid to laud them as the greatest things going -- which, in some cases, they were -- and it was not common during those days to find such uninhibited support for rock among music business types over 30 years in age. And he was able to communicate with artists who were, in some cases, growing increasingly eccentric and antiestablishment, and he was able to do this much more effectively than most publicists and record executives.

In 1968, Taylor reentered the world of the Beatles and held court at Apple as press officer, putting the best face on the financial chaos, tensions within the Beatles, and general madness at the company to the public in the late '60s. It was he who was saddled with issuing a coy press release in April 1970, when the Beatles broke up, that did not exactly deny or confirm that the group had come to an end, writing, "Spring is here and Leeds play Cheshire tomorrow and Ringo and John and George and Paul are alive and well and living in hope. The world is still spinning and so are we and so are you. When the spinning stops, that'll be the time to worry. Not before." After the Beatles split, Taylor worked for Warner Bros., Elektra, and Atlantic, becoming a vice president of Warner Bros. He produced a few albums, the most famous of these being Harry Nilsson's A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night. He left Warner Bros. in the late '70s and helped in the writing of the autobiographies of George Harrison and Michelle Phillips, as well as writing a few memoirs of his own. The best circulated, and best, of these was -It Was Twenty Years Ago Today, which covers the Summer of Love via the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's album and the California psychedelic youth counterculture. It interwove straight reporting with extensive quotes from musicians and other scenesters of the time, as well as his own memories. Like much of Taylor's writing, it was suffused with warm nostalgia, though this was not overbearing enough to make the text uncomfortable.

Taylor returned to Apple Corps in the mid-'80s, and was involved in the archival Beatles projects generated by the company in the '90s, such as the Anthology compilations and video documentary. It is a measure of the respect that the surviving Beatles retained for Taylor that he was one of only three non-Beatles (the others were George Martin and road manager/accountant Neil Aspinall) interviewed for the Anthology series, although frankly there were several other non-Beatles not interviewed who played a much greater role in their art and lives. Derek Taylor died in 1997, after a long illness. ~ Richie Unterberger, Rovi