Poole was born in Randolph County, NC, and spent much of his adult life working in textile mills. He learned banjo as a youth and also played baseball. (He may have adopted his three-finger playing style, a version of classical banjo technique, due to a baseball accident involving his thumb.) When not working in mills, he would travel from town to town across the country, playing the banjo and taking what work he could get. He ended up settling in Spray, NC, in 1918 and married two years later. He and his brother-in-law, fiddler Posey Rorer, would often play together with other local musicians, and out of these performances grew a distinct group called the North Carolina Ramblers. Poole and Rorer teamed up with guitarist Norm Woodlieff in 1925, and the trio auditioned in New York for Columbia Records. They were accepted and cut four songs; all were successful, including the bluesy Don't Let Your Deal Go Down. That became a bluegrass and country standard, and Poole and the Ramblers were soon a popular string band. The band's unusual sound remained consistent through several changes in personnel. As vocalist, Poole sang with a plain, uninflected style that complemented his complex banjo picking. Often, and perhaps intentionally, Poole obscured parts of the lyrics when he sang; record buyers sometimes purchased Ramblers recordings simply so that they could try to parse out what he was saying. The songs they sang were a mixture of minstrel songs, Victorian ballads, and humorous burlesques often delivered with Poole's straight-faced, dry wit. Several more songs' paths to popularity in the country tradition led through Poole's band, including Sweet Sunny South and White House Blues, and his catalog is full of unexpected charmers like If the River Was Whiskey, which deftly weaves that Irish tale of drunkenness with the then-up-to-the-minute Hesitation Blues (also known as Sittin' on Top of the World). Through the rest of the 1920s, the Ramblers recorded close to 70 sides for Columbia.

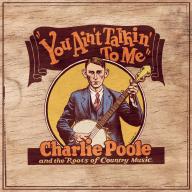

Like many country performers to follow, Poole lived a fast life; he was a hard-drinking man, rowdy and reckless. Poole was significant as one of the first country artists to gain widespread popularity through recordings, and when the Depression slowed record sales dramatically, he was hard hit. Around 1930 his self-confidence began to wane with his popularity, and he began drinking even more heavily. Scheduled to appear in a film in 1931, he unfortunately went on a bender and died of heart failure before he could get to Hollywood. After his death, Rorer (who had left the band in 1929) and guitarist Roy Harvey (who'd replaced Woodlieff around the same time) began leading the North Carolina Ramblers. (The group continued to record and perform for a quite a few years afterward.) Poole's music enjoyed renewed popularity during the folk revival of the '60s, and several reissue LPs followed. His complete recordings were issued on CD by the County label in the 1990s, Kinney Rorrer wrote and published a biography of the great bandleader and banjo player, and Poole received the full Columbia/Legacy treatment in 2005 with the three-disc box-set treasure, You Ain't Talkin' to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music. ~ Sandra Brennan & James Manheim, Rovi