Upon his return from military service, Bowen picked up pretty much where he left off, winning some major prizes and publishing pieces through Chappell, the future Boosey and Hawkes, Chester, Oxford, and Stainer & Bell. But by the mid-'20s Bowen began to run into troubles with reviewers for sloppy keyboard technique and presenting recitals made up entirely of short pieces. In his compositions, Bowen preferred to pursue a predominantly post-romantic path colored to some extent by impressionism -- not wholly unlike his slightly older contemporary Cyril Scott, though certainly with a different approach within that area of endeavor -- and this manner fell increasingly out of favor after 1930. In later years, Bowen continued to teach at RAM and formed a piano duo with another professor, Henry Issacs, which helped restore some measure of acclaim to Bowen as a performer, though his music was forgotten by the time he died at age of 77 in 1961.

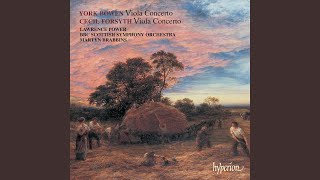

Bowen made his first recording in 1915, but most of his recording activity is concentrated between 1923 and 1927 in records made for British Vocalion; when the company reorganized that year, it appears he did not return to making records except in 1961, when Bowen made a final album for Lyrita. The rebirth of interest in Bowen began in the mid-'80s, largely through the efforts of musicologist Monica Watson; since there has been a York Bowen Society founded and RAM is offering a York Bowen Prize in his honor. Among his compositions, Bowen's Suite in D minor for violin and piano (1909), Fourth Piano Concerto (1929), Symphony No. 3 (1951), and the cycle of works for his friend violist Lionel Tertis, including a concerto (1907) are all regarded as especially significant in addition to some of the shorter piano works, of which there are indeed many. Kaikhosru Sorabji once commented about the "freedom (...) flexibility and elasticity" of Bowen's 24 Preludes, Op. 102 (1938), and dedicated his own Passeggiata veneziana (1955) to Bowen. ~ Uncle Dave Lewis, Rovi