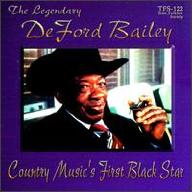

DeFord Bailey

from Bellwood, TN

December 14, 1899 - July 2, 1982 (age 82)

Biography

There is a gulf of Bibilical proportions between the amount of influence American black music has had on country western and the number of black performers actually involved in country. One of the few heroes in what is sadly not a fable is this harmonica player, a victim of infantile paralysis who had to struggle with his physical handicaps as well as racism. The old-time music performer, stooped with a deformed chest, less than five feet tall and weighing under 100 pounds, was for a time a familiar act at the Grand Ole Opry. That is, until a tiff with Opry honcho George Hay led to his dismissal. After that, the only job he could get in country music in Nashville was as a shoeshine man, in itself a step below the often joked about official way of summoning a country songwriter in that town: "waiter!" And even after his death, the fight between Bailey and the Nashville establishment continues, with Roy Acuff bristling at the idea of honoring the man with a membership in the Country Music Hall of Fame, although many other old-time performers of Bailey's generation have already been inducted. After all, it was these original old-time performers who with their personality and unique music had managed to launch what would become an unstoppable institution in country music. Bailey was a professional musician from the age of 14, by which time he was already supporting himself around Smith County, TN, by playing the harmonica. He had also picked up a few other instruments that were required items in country music from his dad and uncle. The music that was being passed around was something Bailey described as black hillbilly, old-time music that was like a bottle of half and half, with the milk country and the cream blues. And nobody listening cared if a particular number had a bit more cream than milk, or vice versa. By the end of 1925 Bailey was good enough on harmonica to place second in a WDAD French Harp Contest. Right around that time he met another harmonica player, Dr. Humphrey Bate, who was both a country physician and musician. It was Bate who would bring his fellow harp player to the attention of the Opry and its promotion genius George Hay. Bate and his group had been performers on the first broadcast of the Opry, and his relationship with the management was typical of the effect Hay and his ilk would have on the cultural perception of country music. When Bate had arrived at the studio for this premier Opry broadcast, his group was known as the Augmented Orchestra, as it featured doubles of instruments such as guitar and fiddle. But when the group appeared on the air, it was announced as Dr. Humphrey Bate and His Possum Hunters. The name was a concoction of Hay, who literally made hay selling old-time music dressed up in hillbilly clothes. Hay's first reaction to a slightly hunchbacked height-challenged black harmonica player was apparently not one of high enthusiasm. Bate pressed firmly on the subject of Bailey, however, and perhaps the doc's medical credentials intimidated Hay. Bailey was given a chance and went on to become the Opry's first solo star as well as its first black artist. Historians lobbying for Bailey's importance go on to point out that in 1928, the Opry's first year, the harmonica player did his thing on 49 of the 52 programs. No other artist even came close to that record of appearances. A symbolically more important event was the fact that immediately after the audience heard the phrase Grand Ole Opry announced for the very first time, on came Bailey blowing his train imitation on the harp. He remained secure in this contract with the Opry for about 15 years. He recorded in the late '20s on labels such as Columbia, Brunswick, and Victor. His sessions were the first decently recorded examples of harmonica playing and were incredibly influential. His effect on the history of the instrument itself is measurable, because his success led to opportunities for many other harmonica players to record and perform. Pan American Blues was one of his most popular numbers along with John Henry. Bailey complained about never receiving royalties for these sides, which were re-released steadily through 1936, then began showing up on old-time and classic country compilations from the '70s onward. In the '30s Bailey was involved in many tours, including a package show with old-time legend Uncle Dave Macon. Bailey helped establish several performers by appearing as a solo artist in front of their bands, including Roy Acuff. Venues at this time included tent shows and county fairs as well as theatres. Wherever the tour might lead, Bailey always had to be back in Nashville for the Saturday night Opry show. Since his pay was only five dollars, this situation often meant he was losing money arriving for his Opry shows. There are articles that also claim his rate of pay reflected racist practices, but accounts of other Opry artists from this era have mentioned this as a basic rate for all the artists. One thing is beyond question. Bailey was forced to eat and sleep separately from his fellow Opry artists due to segregation. The number of black country artists has remained negligible, in fact they could be packed into a small car and still have room for Ernest Tubb's merchandise setup. The next one allowed on the Opry after Bailey would be Charlie Pride. Why the Opry gave Bailey the hook is often described as a matter of dispute, but the reality of the situation is pretty apparent from remarks made by Hay in his memoirs. "Like some members of his race, DeFord was lazy. He knew about a dozen numbers, which he put on the air and recorded for a major company, but he refused to learn any more." The truth is that many old-time musicians worked from a fixed repertoire, and were not interested in adding material beyond that. Of course this creates problems for record producers, publishers, or other music investors attempting to acquire copyrights. The way to insure the survival of different types of traditional music is of course to provide performing situations for its practitioners, regardless of how many new titles might be added to their song list in a given year. The Opry management didn't see this, however. He was invited back to the Opry for an old-timer's show in 1974, at which time he apparently blew up a storm. In between he cooled his heels while polishing other people's, working at a shoeshine stand he had opened with his uncle in 1933. He lived in the I.W. Gernert Homes, not far from the shoeshine stand, when he died four years after the final Opry show. So far the official Hall of Fame line is that although he will be remembered fondly for his contributions to the show, these contributions do not warrant a place in the Country Music Hall of Fame. Several music organizations and individuals who were fans of Bailey's continue to lobby on his behalf. ~ Eugene Chadbourne, Rovi

Top Tracks

Albums

Videos

Close