Carl Lee Perkins was born in 1932 in Tipton, Tennessee to sharecroppers Buck and Louise Perkins (misspelled on his birth certificate as "Perkings"). Starting early in his childhood, he worked in the fields picking cotton and living in a shack with his parents, older brother Jay, and his younger brother Clayton. Gifted a second-hand guitar, he took lessons from a local Black sharecropper, learning firsthand the boogie rhythm that he would later build a career on. By his teens, Perkins was playing electric guitar, mixing R&B traditions with bluegrass and country techniques. He soon recruited his brothers Jay on vocals and rhythm guitar and Clayton on vocals and string bass. The Perkins Brothers Band quickly established itself as the hottest band in the get-hot-or-go-home cutthroat Jackson, Tennessee honky tonk circuit. It was here that Carl started composing his first songs with an eye toward the future. Watching the dancefloor at all times for a reaction, Perkins kept reshaping these loosely structured songs until he had a completed composition, which would then finally be put to paper. He was already sending demos to New York record companies, who kept rejecting him, sometimes explaining that this strange new hybrid of country and R&B fit no current commercial trend. But once Perkins heard Elvis on the radio, he not only knew what to call it, but knew that there was a record company person who finally understood it and was also willing to gamble on promoting it. That man was Sam Phillips and the record company was Sun Records, and that's exactly where Perkins headed in 1954 to get an audition.

It was here at his first Sun audition that the structure of the Perkins Brothers Band changed forever. Phillips didn't show the least bit of interest in Jay's Ernest Tubb-styled vocals but flipped over Carl's singing and guitar playing. A scant four months later, he had issued the first Carl Perkins record, "Movie Magg"/"Turn Around," both sides written by the artist. By his second session, he had added W.S. Holland -- a friend of Clayton's -- to the band playing drums, a relatively new innovation to country music at the time. Phillips was still channeling Perkins in a strictly hillbilly vein, feeling that two artists doing the same type of music (in this case, Elvis and rockabilly) would cancel each other out. But after selling Elvis' contract to RCA Victor in December, Perkins was encouraged to finally let his rocking soul come up for air at his next Sun session. And rock he did, with a double-whammy blast that proved to be his ticket to the bigs. The chance overhearing of a conversation at a dance one night between two teenagers, coupled with a song idea suggestion from labelmate Johnny Cash, inspired Perkins to approach Phillips with a new song he had written called "Blue Suede Shoes." After cutting two sides that Phillips planned on releasing as a single by the Perkins Brothers Band, Perkins laid down three takes each of "Blue Suede Shoes" and another rocker, "Honey Don't." A month later, Phillips decides to shelve the two country sides and go with the rockers as Perkins' next single. Three months later, "Blue Suede Shoes," a tune that borrowed stylistically from pop, country, and R&B music, sat at the top of all charts, the first record to accomplish such a feat while becoming Sun's first million-seller in the bargain.

Ready to cash in on a national basis, Perkins and the boys headed up to New York for the first time to appear on The Perry Como Show. While en route their car rammed the back of a poultry truck, putting Carl and his brother Jay in the hospital with a cracked skull and broken neck, respectively. While in traction, Perkins saw Presley performing his song on The Dorsey Brother Stage Show, his moment of fame and recognition snatched away from him. Perkins shrugged his shoulders and went back to the road and the Sun studios, trying to pick up where he left off.

The follow-ups to "Shoes" were, in many ways, superior to his initial hit, but each succeeding Sun single held diminishing sales, and it wasn't until the British Invasion and the subsequent rockabilly revival of the early '70s that the general public got to truly savor classics like "Boppin' the Blues," "Matchbox," "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby," "Your True Love," "Dixie Fried," "Put Your Cat Clothes On," and "All Mama's Children." While labelmates Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis (who played piano on "Matchbox" during the legendary Million Dollar Quartet session) were scoring hit after hit, Perkins was becoming disillusioned with his fate, fueled by his increasing dependence on alcohol and the death of his brother Jay to cancer. He kept plugging along, and when Cash left Sun to go to Columbia in 1958, Perkins followed him over. The royalty rate was better, and Perkins had no shortage of great songs to record, but Columbia's Nashville watch-the-clock production methods killed the spontaneity that was the charm of the Sun records.

By the early '60s, after being dropped by Columbia and moving over to Decca with little success, Perkins was back playing the honky tonks and contemplating getting out of the business altogether. A call from a booking agent in 1964 offering a tour of England alongside Chuck Berry changed all of that. Temporarily swearing off the bottle, Perkins was greeted in Britain as a conquering hero, playing to sold-out audiences and being particularly lauded by a young beat group on the top of the charts named the Beatles. George Harrison had cut his musical teeth on Perkins' Sun recordings (as had most British guitarists) and the Fab Four ended up recording more tunes by him than any other artist except themselves. The British tour not only rejuvenated his outlook, but suddenly made him realize that he had gone -- through no maneuvering of his own -- from has-been to legend in a country he had never played in before. Upon his return to the States, he hooked up with old friend and former labelmate Cash and was a regular fixture of his road show for the next ten years, bringing his battle with alcohol to an end. He kept recording, releasing My Kind of Country in 1973 and covering classic rock & roll and country hits on 1978's Ol' Blue Suede's Back.

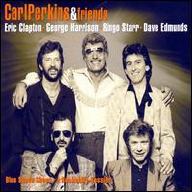

As the '80s dawned, Perkins found himself at the epicenter of the rockabilly revival, touring on his own with a new band consisting of his sons backing him (including future Rockabilly Hall of Famer Stan Perkins). In 1982, he collaborated with Paul McCartney on the song "Get It," included on Tug of War. He also joined with Stray Cats members Lee Rocker and Slim Jim Phantom for a re-recording of "Blue Suede Shoes" for the soundtrack to the comedy Porky's Revenge. 1985 proved a banner year for Perkins, who was featured in a live television special, Blue Suede Shoes: A Rockabilly Session, recorded at London's Limehouse Studios and featuring guests including George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Dave Edmunds, Rosanne Cash, and Ringo Starr. He also made a cameo, alongside David Bowie, in director John Landis' film Into the Night. 1985 was also the year he was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. Two years later, he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and, soon after, the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. In 1986, his original 1955 recording of "Blue Suede Shoes" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. That same year, he reunited with fellow rock & roll legends Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison for Class of '55: Memphis Rock Roll Homecoming, a tribute to their early years at Sun Records. In 1989, he scored a number one country hit with the Judds on "Let Me Tell You About Love" and released his own album, Born to Rock.

In 1992, Perkins released Friends, Family, Legends, a star-studded production featuring appearances by Chet Atkins, Travis Tritt, Joan Jett, Charlie Daniels, Paul Shaffer, and others. He then collaborated with Duane Eddy and the Mavericks, contributing a version of "Matchbox" to the 1994 AIDS benefit album Red Hot + Country. Perkins' final album, Go Cat Go!, arrived in 1996 and featured guest spots from many performers who had drawn inspiration from him, including both George Harrison and Paul McCartney, Bono, John Fogerty, and Tom Petty, among others. After a long battle with throat cancer, Perkins died in early 1998 at the age of 65, his place in the history books assured. ~ Matt Collar & Cub Koda, Rovi