Guido Cantelli's musical ability manifested itself before he could read. Born in the small town of Novara near Milan, he was already playing the piano at age six and giving impromptu concerts. At age eight, he was already able to make decisions about musical interpretation for other members of his family, and by nine he was directing the local church choir in Novara. Ironically, it was as a student of composition that he started his formal musical training at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan, but he never moved far from conducting, and he made his debut at the operatic podium in 1943 at the Teatro Coccia in Novara.

Cantelli ran into legal trouble in 1943 when he refused to enlist in the Italian army. Soon afterward, however, he was imprisoned in a Nazi labor camp on the Baltic coast, from which he had to escape using forged papers. He returned to Novara and slowly regained his health while working in a bank, according to some stories, under an assumed name.

He resumed his career after the end of the war, and was fortunate enough to attract the notice of the reigning giant of the podium, not only in Italy but throughout the world, Arturo Toscanini. The bond between the two men was established from the moment that Toscanini heard him conduct in 1948. The older maestro immediately arranged for Cantelli to make his American debut as guest conductor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1948. Toscanini continued to aid Cantelli, nearly 60 years his junior, with advice and recommendations to other orchestras, and the entire musical world lay at the younger man's feet. In 1950, he made his English debut at the Edinburgh Festival, with the La Scala Orchestra, and in 1951 he conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra of London for the first time. This and the concerts that followed led to a series of studio recordings that have since taken on legendary status.

Cantelli's attention to detail, and his persuasiveness with an orchestra, were evident in the surviving recordings and radio broadcasts. He could spend 45 minutes running through just the first page of a difficult score, as was the case with Debussy's The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, but in the end, the performance would sound fresh, open, and completely spontaneous -- and would rival any performance by a French orchestra, no small feat for an English ensemble being led by an Italian conductor. He was described by one witness to his recording sessions as a "possessed conductor."

He could put an orchestra through more than a dozen takes of a piece that they had played in concert only days before, in pursuit of perfection, and was also prone to the occasional burst of temper. On a purely personal level, he had a boyish exuberance but also displayed a remote nature, that at times left him seemingly detached from those around him. Yet he was, in retrospect, extremely popular with the members of every orchestra that he worked with.

His approach to music was remarkably similar to that of Toscanini. Cantelli emphasized fidelity to the score as written, in terms of tempo and detail, and he downplayed what he regarded as the subjective emotionalism that characterized the work of most conductors of the era.

Cantelli was extremely popular in New York, not only with the NBC Symphony which, it was assumed, he might eventually take over from Toscanini, who had retired in 1954, but also with the New York Philharmonic, which reportedly was considering him as a potential replacement for Dimitri Mitropoulos, their extremely talented but embattled chief conductor. He had been engaged by the Philharmonic as a guest conductor for a concert in late November of 1956, and was on his way from Rome when the plane he was on crashed outside of Paris on November 24, 1956, during a refueling stop. The 88-year-old Toscanini, who lived only a few more months, was supposedly never told of Cantelli's death.

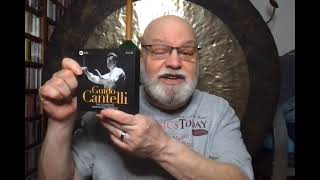

He left behind a magnificent series of recordings and radio broadcasts, many of which have since surfaced on various "private label" releases. Alas, his recording career only spanned about eight years, and he never got to set down complete cycles of any composer's work -- his legacy includes a magnificent Beethoven Symphony No. 7, a beautifully shaped Schubert Unfinished Symphony, a superb recording of the Mozart Symphony No. 29, a large body of Debussy's orchestral music the quality of which has seldom been rivaled, a beautiful, powerful Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6, and an even better Romeo and Juliet. The saddest, and strangest of all his remaining studio recordings is a tragically unfinished Beethoven Symphony No. 5 -- because of interruptions due to construction, Cantelli and the Philharmonia were only able to record the movements two through four; it was his intention to complete the first movement upon his return to London, which never happened; this incomplete recording has been released, and listening to it is an experience akin to watching the "performance" of the Red Shoes ballet at the end of the movie The Red Shoes, as the spotlight hits all the marks that the now-dead Victoria Page was to have hit in her performance. In addition to several radio broadcast performances that have appeared in recent years, Cantelli's work with the New York Philharmonic includes a performance of Vivaldi's The Four Seasons (then not remotely the Baroque warhorse that it has since become) that has remained a perennially popular historical recording. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi