He was born Erich Landauer in Vienna, Austria, and by the age of five was enrolled in a local music school, beginning piano studies at age eight. He subsequently studied at the music department of the University of Vienna, and from 1931 until 1933 took courses at the Vienna Conservatory, making his debut at the podium at the Musikvereinsaal upon graduation. He became the assistant conductor of the Workers' Chorus in Vienna in 1933, and a year later successfully auditioned before Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival, where he was appointed an assistant, serving under Toscanini.

Leinsdorf was engaged by the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1937, and his American debut took place there, at age 25, when he conducted Wagner's Die Walkure on Jan. 21 of 1938. His success with other Wagner operas led to his appointment at the Met in 1939 as head of the company's German repertoire. It was while at the Met that he began developing a reputation as a strict taskmaster, demanding more rehearsal time from his singers and extremely precise fidelity to the written score by his orchestras--although the audiences appreciated the results he achieved, many of the singers he worked with were highly critical of his work and the demands he made upon them.

He took American citizenship in 1942, and the following year he was appointed music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. He had no time to achieve much in the new post, however, as Leinsdorf was inducted into the United States Army in December of that year. He was discharged in 1944, and returned to the Met, where he conducted during the 1944-45 season. During 1945 and 1946, he also conducted the Cleveland Orchestra on several occasions, and returned to Europe where, as one of a group of major Austrian-born conductors who had no connections with the Nazis, he was engaged to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. He found his reception in the city of his birth, first overrun by the Nazis, then bombed and invaded by the Allies and starved in the immediate wake of World War II, however, to be less than entirely cordial.

By 1947, he was back in the United States as music director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in upstate New York, a post he held until 1955. Leinsdorf served as music director of the New York City Opera for part of 1956, before returning to the Met as a conductor and musical consultant, amid numerous guest conductor assignments in America and Europe. In 1962, Leinsdorf succeeded to one of the most prestigious musical posts in America, as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, succeeding Charles Munch. Leinsdorf's tenure at Boston was extremely productive but stormy. He found the political considerations of a music directorship, juggling the demands of individual musicians, their unions and existing work and rehearsal rules, and the board of directors, to be a distraction from his musical goals. Additionally, it was during this period that Leinsdorf became known for being openly critical of the shortcomings, in terms of education, of the musicians working under him (especially gaps in their cultural educations), errors in published scores of established musical works, and the errors made by his fellow conductors.

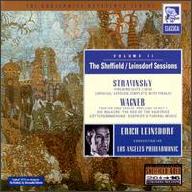

He resigned the Boston post with the 1968-69 season, happy to have served in one of the most exalted musical positions in the United States, but equally happy, in his own words, to have exited with his health intact. Leinsdorf conducted opera and concert performances throughout the United States and Europe for the next two decades, including work with the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic. In 1978, he took up his first permanent post in Europe, was principal conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra in West Berlin, a post he held until 1980. In 1976, he published Cadenza: A Musical Career, a memoir that was as noted for its candid, brutally honest assessments of himself and his fellow musicians as for the biographical details it offered. He continued recording until the final years of his performing career, at the end of the 1980's, including audiophile digital performances of Wagner orchestral music for the Sheffield Labs label.

Erich Leinsdorf's greatest operatic achievements on record, Turandot and Madame Butterfly, remain in print on compact disc more than 30 years after they were recorded, but his orchestral recordings haven't fared as well. Mostly confined to RCA/BMG with the Boston Symphony, a relative handful of these have appeared on budget CD reissues (mostly BMG's "Silver Seal" label), including a Mahler Fifth Symphony that is no longer really competitive with other versions out there (at the time it was recorded in the mid-1960's, it was one of perhaps four or five versions, not one of 60 as it is today); ironically, his Mahler Symphony No. 3, one of the finest things he ever did, and one of the better performances of this monumental work ever done, remains out-of-print, and well worth owning on vinyl. ~ Bruce Eder

Mahler Symphony No. 5 RCA/BMG [5]

Symphony No. 3RCA [8] (out-of-print)

MozartDon GiovanniLondon [7]

Puccini Madame ButterflyRCA/BMG [7]

TurandotRCA/BMG [8], Rovi