The group's history dates back to 1958. Ronnie Hawkins, an Arkansas-born rock & roller who aspired to a real career, assembled a backing band that included his fellow Arkansan Levon Helm, who played drums (as well as credible guitar) and had led his own band, the Jungle Bush Beaters. The new outfit, Ronnie Hawkins the Hawks, began recording during the spring of 1958 and gigged throughout the American south; they also played shows in Ontario, Canada, where the money was better. When pianist Willard Jones left the lineup one year later, Hawkins began looking at some of the local music talent in Toronto in late 1959. He approached a musician named Scott Cushnie about joining the Hawks on keyboards. Cushnie was already playing in a band with Robbie Robertson, however, and would only join Hawkins if the latter musician could come along.

After some resistance from Hawkins, Robertson entered the lineup on bass, replacing a departing Jimmy Evans. Additional lineup switches took place over the next few years, with Robbie Robertson shifting to rhythm guitar behind Fred Carter's (and, briefly, Roy Buchanan's) lead playing. Rick Danko came in on bass in 1961, followed by Richard Manuel on piano and backing vocals. Around that same time, Garth Hudson, a classically trained musician who could read music, became the last piece of the initial puzzle as organ player. From 1959 through 1963, Ronnie Hawkins the Hawks were one of the hottest rock & roll bands on the circuit, a special honor during a time in which rock & roll was supposedly dead. The mix of personalities within the group meshed well, better than they did with Hawkins, who, unbeknownst to him, was soon the odd man out in his own group. As new members Danko, Manuel, and Hudson came aboard -- all Canadian, replacing Hawkins' fellow Southerners -- Hawkins lost control of the group as they began working together more closely.

The Hawks parted company with Ronnie Hawkins during the summer of 1963. They decided to stay together with their oldest member, Levon Helm, out in front, variously renaming themselves Levon the Hawks and the Canadian Squires, and cutting records under both names. A hook-up with a young John Hammond, Jr. for a series of recording sessions in New York led to the group being introduced to Bob Dylan, who was then preparing to pump up his sound in concert. Robertson and Helm played behind Dylan at his Forest Hills concert in New York in 1965 (a bootleg tape of which survives), and he ultimately signed up the entire group.

The hook-up with Dylan changed the Hawks, but it wasn't always an easy collaboration. They'd learned to play tightly and precisely and were accustomed to performing in front of audiences that were interested primarily in having a good time and dancing. Dylan, however, was playing for crowds that seemed ready to reject him on principle, as he forsook acoustic folk for tough, loud rock & roll. The Hawks weren't accustomed to confronting the kinds of passions that drove the folk audience, any more than they were initially prepared for the freewheeling nature of Dylan's performances -- he liked to make changes in the way he played songs on the spot, and the group was often hard put to keep up with him, at least at first, although the experience did make them a more flexible ensemble on-stage.

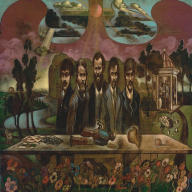

The group performed as Dylan's backup band on his 1966 tour, although Levon Helm, aggravated by the negative reactions of the audiences, left soon after the tour began. The group ultimately fell under the orbit of Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, who persuaded the four core members (sans Helm) to join Dylan in Woodstock, New York, to work on the sessions that ultimately became The Basement Tapes in their various configurations, none of which would be heard officially for almost a decade. Finally, a recording contract for the group -- rechristened the Band -- was secured by Grossman from Capitol Records. Levon Helm returned to the fold, and the result was Music from Big Pink, an indirect outgrowth of the Basement Tapes. This album, enigmatically named and packaged, sounded like nothing else being done by anybody in music when it was released in July of 1968. It was as though psychedelia, and the so-called British Invasion, had never happened; the group played and sang like five distinct individuals working toward the same goal of mixing folk, blues, gospel, R&B, classical, and rock & roll. Their music was steeped in Americana and historical and mythic American imagery, despite the fact that all of the members except Helm came from Canada. Robertson, Manuel, and Danko all wrote, and everyone but Robertson and Hudson sang; their vocals didn't mesh sweetly but simply flowed together in an informal manner. Classical organ flourishes meshed with a big (yet lean), raw rock & roll sound and the whole was so far removed from the self-indulgent virtuosity and political and cultural posturing going on around them that the Band seemed to be operating in a different reality, with different rules.

Meanwhile in 1969, the first widely distributed bootleg LP, The Great White Wonder, featuring the then-unreleased Basement Tapes, started turning up on college campuses and record collectors' outlets. The quality was poor, the labels were blank, but it got around to hundreds of thousands of listeners and only heightened the mystique surrounding the Band. A second album, simply titled The Band, was every bit as good as the first. Dominated by Robertson's writing, it was released in September of 1969, and with it, the group's reputation exploded; moreover, they began their climb out of the shadow of Bob Dylan with songwriting of their own that was every bit a match for anything he was releasing at the time. A pair of songs, "Up on Cripple Creek" and "The Night They Drove Ol' Dixie Down," captured the public imagination, with the former getting them onto The Ed Sullivan Show.

Following the release of the second album, things changed somewhat within the group, partly owing to the pressures of touring, the public's expectations of "genius," and the growing press focus on Robbie Robertson at the expense of the rest of the group. The Band were still a great working ensemble, as represented on their third album, Stage Fright, but gradually exhaustion and personal pressures took their toll. Additionally, the members had always engaged in casual drug use, mostly involving marijuana, but now they had access to more serious and expensive chemical diversions. Some private resentments also began manifesting themselves about Robertson's dominance of the songwriting (some of which was questioned openly in Levon Helm's autobiography years later), and the fact that the group was now constantly in the public eye didn't help. By the time of their fourth album, Cahoots, some of the glow of experimentation and easygoing camaraderie had faded, though the album was still one of the best they released in 1971. The problem for the group became fulfilling the commitments involved in success, including touring and writing new material to record. By the end of 1971, they'd decided to take a break, cutting a live album, Rock of Ages; their next effort, 1973's Moondog Matinee, was a collection of studio versions of the oldies that the group used to do on-stage in their days as the Hawks, and should have been a warning sign that not everything was well within the band. They didn't tour behind the record, but played one major show that year, at the race track at Watkins Glen, New York. Booked alongside the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers Band, they performed before the largest audience ever assembled for a rock concert.

1973 was also the year they renewed their association with Bob Dylan, backing him on his album Planet Waves and preparing for a huge national tour together in 1974. That tour, in retrospect, seemed more a basis for cashing in on their association with Dylan than for any new music-making of any significance. In many critics' eyes, the Band were in better form than Dylan in their performances, a notion borne out on the live LP Before the Flood that was distilled from two February 1974 performances. Another album, Northern Lights-Southern Cross, released in late 1975, was a major comeback and restored some of the group's reputation as a cutting-edge ensemble. Around this same time, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson made a belated contribution to the history of Chess Records when they worked with Muddy Waters, cutting an entire album with the blues legend at Helm's studio in Woodstock, New York. Overlooked on release, The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album was the last great album Waters cut for the label, and his best album in at least five years.

In 1976, the Band were coming apart as a working ensemble, with the various members involved in their own interests and lives, and little live work. A "best-of" album was released, and they set out on tour, but Robertson felt their days were numbered as a group on the road, and he made the decision to stage a gala farewell concert at San Francisco's Winterland on Thanksgiving Day, 1976. A bevy of guest stars agreed to appear, including Ronnie Hawkins, Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, and Bob Dylan, and Martin Scorsese was recruited to film the show for posterity. The concert was covered widely in the rock press in 1976, but its status as a major event was retroactively sealed when Scorsese's film, titled The Last Waltz, was released in 1978, in tandem with a three-LP soundtrack album. The documentary was widely hailed as one of the finest concert films ever released, but by the time it arrived in theaters, the Band's final album, 1977's Islands, had fallen on deaf ears, while Danko and Helm released solo LPs, and Robertson dabbled in acting and film scoring.

Robertson intended for the Band to keep working together in the studio after the farewell show, but as he became involved in other projects, the group stopped being one of his priorities. The other members of the group were less interested in getting off the road than Robertson (which Helm stated in no uncertain terms in his autobiography), and in 1983 they reunited for a concert tour with members of the Cate Brothers Band filling in for the absent Robertson (who gave the reunion his blessing). The Band continued to tour on and off for the next several years, though on March 4, 1986, Richard Manuel (who had struggled for years with drug and alcohol addiction) committed suicide after a performance in Winter Park, Florida. Despite Manuel's absence, Helm, Danko, and Hudson kept up their touring schedule with a rotating cast of new members, and in 1993 released an album, Jericho, that along with fresh studio material included an unreleased live performance of Richard Manuel singing "Country Boys." Meanwhile, Robertson honored Manuel with the song "Fallen Angel" that appeared on his first solo effort, Robbie Robertson, released in 1987.

In 1994, the Band were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and Robertson, Danko, and Hudson performed together at the award ceremony; Helm, who was at odds with Robertson over songwriting credits and what he felt was unfair distribution of royalties, opted not to attend. With Helm, the Band stayed on the road, and they issued more studio albums, with High on the Hog arriving in 1996 and Jubilation following in 1998. In 1999, they recorded a cover of Bob Dylan's "One Too Many Mornings" for a tribute album, Tangled Up in Blues: Songs of Bob Dylan. It would prove to be the last recording they would release, as Rick Danko died on December 10, 1999, at the age of 55. Following Danko's passing, the Band finally retired.

Levon Helm, who balanced his musical career with occasional acting gigs, was diagnosed with throat cancer in the late '90s, and as he sought treatment, he began hosting regular performances at the recording studio on his property in Woodstock, New York, and the "Midnight Ramble" shows gave his solo career new life. In 2007, Helm issued a studio LP, Dirt Farmer, that earned him a Grammy award for Best Traditional Folk Album, and a more rollicking follow-up, Electric Dirt, appeared in 2009. Though Helm's cancer returned, he was still performing less than three weeks before his death on April 19, 2012. Garth Hudson pursued a low-key solo career, occasionally performing in person and releasing The Sea to the North in 2001, and in 2011 he issued Garth Hudson Presents a Canadian Celebration of the Band, in which he sat in with a variety of artists interpreting songs from throughout the group's career. Robbie Robertson recorded periodically, served as an A&R executive for Dreamworks Records, and collaborated frequently with Martin Scorsese, composing and coordinating music for Raging Bull, The King of Comedy, The Color of Money, The Departed, and many more. The Band's legacy lived on through a series of archival releases, chief among them the comprehensive 2005 box set A Musical History and lavish 50th anniversary editions of Music from Big Pink, The Band, and Stage Fright. In 2021, a Deluxe Edition of Cahoots was released that presented the album with a new mix by Bob Clearmountain, and featured a previously unreleased live concert recorded in Paris, France in May 1971. ~ Bruce Eder & Mark Deming, Rovi