Like many of his contemporaries on the Chicago circuit, Waters was a product of the fertile Mississippi Delta. Born McKinley Morganfield in Rolling Fork, he grew up in nearby Clarksdale on Stovall's Plantation. His idol was the powerful Son House, a Delta patriarch whose flailing slide work and intimidating intensity Waters would emulate in his own fashion.

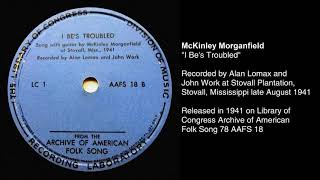

Musicologist Alan Lomax traveled through Stovall's in August of 1941 under the auspices of the Library of Congress, in search of new talent for the purpose of field recording. With the discovery of Morganfield, Lomax must have immediately known he'd stumbled across someone very special.

Setting up his portable recording rig in the Delta bluesman's house, Lomax captured for Library of Congress posterity Waters' mesmerizing rendition of I Be's Troubled, which became his first big seller when he recut it a few years later for the Chess brothers' Aristocrat logo as I Can't Be Satisfied. Lomax returned the next summer to record his bottleneck-wielding find more extensively, also cutting sides by the Son Simms Four (a string band that Waters belonged to).

Waters was renowned for his blues-playing prowess across the Delta, but that was about it until 1943, when he left for the bright lights of Chicago. A tiff with "the boss man" apparently also had a little something to do with his relocation plans. By the mid-'40s, Waters' slide skills were becoming a recognized entity on Chicago's South side, where he shared a stage or two with pianists Sunnyland Slim and Eddie Boyd and guitarist Blue Smitty. Producer Lester Melrose, who still had the local recording scene pretty much sewn up in 1946, accompanied Waters into the studio to wax a date for Columbia, but the urban nature of the sides didn't electrify anyone in the label's hierarchy and remained unissued for decades.

Sunnyland Slim played a large role in launching the career of Muddy Waters. The pianist invited him to provide accompaniment for his 1947 Aristocrat session that would produce Johnson Machine Gun. One obstacle remained beforehand: Waters had a day gig delivering Venetian blinds. But he wasn't about to let such a golden opportunity slip through his talented fingers. He informed his boss that a fictitious cousin had been murdered in an alley, so he needed a little time off to take care of business.

When Sunnyland was finished that auspicious day, Waters sang a pair of numbers, Little Anna Mae and Gypsy Woman, that would become his own Aristocrat debut 78. They were rawer than the Columbia stuff, but not as inexorably down-home as I Can't Be Satisfied and its flip, I Feel Like Going Home (the latter was his first national RB hit in 1948). With Big Crawford slapping the bass behind Waters' gruff growl and slashing slide, I Can't Be Satisfied was such a local sensation that even Muddy Waters himself had a hard time buying a copy down on Maxwell Street.

He assembled a band that was so tight and vicious on-stage that they were informally known as the Headhunters; they'd come into a bar where a band was playing, ask to sit in, and then "cut the heads" of their competitors with their superior musicianship. Little Walter, of course, would single-handedly revolutionize the role of the harmonica within the Chicago blues hierarchy; Jimmy Rogers was an utterly dependable second guitarist and Baby Face Leroy Foster could play both drums and guitar. On top of their instrumental skills, all four men could powerfully sing.

1951 found Waters climbing the RB charts no less than four times, beginning with Louisiana Blues and continuing through Long Distance Call, Honey Bee, and Still a Fool. Although it didn't chart, his 1950 classic Rollin' Stone provided a certain young British combo with a rather enduring name. Leonard Chess himself provided the incredibly unsubtle bass drum bombs on Waters' 1952 smash She Moves Me.

Mad Love, his only chart bow in 1953, is noteworthy as the first hit to feature the rolling piano of Otis Spann, who would anchor the Waters aggregation for the next 16 years. By this time, Foster was long gone from the band, but Rogers remained and Chess insisted that Walter -- by then a popular act in his own right -- make nearly every Waters session into 1958 (why breakup a winning combination?). There was one downside to having such a peerless band: As the ensemble work got tighter and more urbanized, Waters' trademark slide guitar was largely absent on many of his Chess waxings.

Willie Dixon was playing an increasingly important role in Muddy Waters' success. In addition to slapping his upright bass on Waters' platters, the burly Dixon was writing one future bedrock standard after another for him: I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man, Just Make Love to Me, and I'm Ready; all seminal performances and each blasted to the uppermost reaches of the RB lists in 1954.

When labelmate Bo Diddley borrowed Waters' swaggering beat for his strutting I'm a Man in 1955, Muddy turned around and did him tit for tat by reworking the tune ever so slightly as Mannish Boy and enjoying his own hit. Sugar Sweet, a pile-driving rocker with Spann's 88s anchoring the proceedings, also did well that year. 1956 brought three more RB smashes: Trouble No More, Forty Days Forty Nights, and Don't Go No Farther.

But rock roll was quickly blunting the momentum of veteran blues aces like Waters; Chess was growing more attuned to the modern sounds of Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, the Moonglows, and the Flamingos. Ironically, it was Muddy Waters who had sent Berry to Chess in the first place.

After that, there was only one more chart item, 1958's typically uncompromising (and metaphorically loaded) Close to You. But Waters' Chess output was still of uniformly stellar quality, boasting gems like Walking Thru the Park (as close as he was likely to come to mining a rock roll groove) and She's Nineteen Years Old, among the first sides to feature James Cotton's harp instead of Walter's, in 1958. That was also the year Muddy Waters and Spann made their first sojourn to England, where his electrified guitar horrified sedate Britishers accustomed to the folksy homilies of Big Bill Broonzy. Perhaps chagrined by the response, Waters paid tribute to Broonzy with a solid LP of his material in 1959.

Cotton was apparently the bandmember who first turned Muddy on to Got My Mojo Working, originally cut by Ann Cole in New York. Waters' 1956 cover was pleasing enough but went nowhere on the charts. But when the band launched into a supercharged version of the same tune at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, Cotton and Spann put an entirely new groove to it, making it an instant classic (fortuitously, Chess was on hand to capture the festivities on tape).

As the 1960s dawned, Waters' Chess sides were sounding a trifle tired. Oh, the novelty thumper Tiger in Your Tank packed a reasonably high-octane wallop, but his adaptation of Junior Wells' Messin' With the Kid (as Messin' With the Man) and a less-than-timely Muddy Waters Twist were a long way removed indeed from the mesmerizing Delta sizzle that Waters had purveyed a decade earlier.

Overdubbing his vocal over an instrumental track by guitarist Earl Hooker, Waters laid down an uncompromising You Shook Me in 1962 that was a step in the right direction. Drummer Casey Jones supplied some intriguing percussive effects on another 1962 workout, You Need Love, which Led Zeppelin liked so much that they purloined it as their own creation later on.

In the wake of the folk-blues boom, Waters reverted to an acoustic format for a fine 1964 LP, Folk Singer, that found him receiving superb backing from guitarist Buddy Guy, Dixon on bass, and drummer Clifton James. In October, he ventured overseas again as part of the Lippmann and Rau-promoted American Folk Blues Festival, sharing the bill with Sonny Boy Williamson, Memphis Slim, Big Joe Williams, and Lonnie Johnson.

The personnel of the Waters band was much more fluid during the 1960s, but he always whipped them into first-rate shape. Guitarists Pee Wee Madison, Luther Snake Boy Johnson, and Sammy Lawhorn, harpists Mojo Buford and George Smith, bassists Jimmy Lee Morris and Calvin Fuzz Jones, and drummers Francis Clay and Willie Big Eyes Smith (along with Spann, of course) all passed through the ranks.

In 1964, Waters cut a two-sided gem for Chess, The Same Thing/You Can't Lose What You Never Had, that boasted a distinct 1950s feel in its sparse, reflexive approach. Most of his subsequent Chess catalog, though, is fairly forgettable. Worst of all were two horrific attempts to make him a psychedelic icon. 1968's Electric Mud forced Waters to ape his pupils via an unintentionally hilarious cover of the Stones' Let's Spend the Night Together (session guitarist Phil Upchurch still cringes at the mere mention of this album). After the Rain was no improvement the following year.

Partially salvaging this barren period in his discography was the Fathers and Sons project, also done in 1969 for Chess, which paired Muddy Waters and Spann with local youngbloods Paul Butterfield and Mike Bloomfield in a multigenerational celebration of legitimate Chicago blues.

After a period of steady touring worldwide but little standout recording activity, Waters' studio fortunes were resuscitated by another of his legion of disciples, guitarist Johnny Winter. Signed to Blue Sky, a Columbia subsidiary, Waters found himself during the making of the first LP, Hard Again, backed by pianist Pinetop Perkins, drummer Willie Smith, and guitarist Bob Margolin from his touring band, Cotton on harp, and Winter's slam-bang guitar, Waters roared like a lion who had just awoken from a long nap.

Three subsequent Blue Sky albums continued the heartwarming back-to-the-basics campaign. In 1980, his entire combo split to form the Legendary Blues Band; needless to note, he didn't have much trouble assembling another one (new members included pianist Lovie Lee, guitarist John Primer, and harpist Mojo Buford).

By the time of his death in 1983, Muddy Waters' exalted place in the history of blues (and 20th century popular music, for that matter) was eternally assured. The Chicago blues genre that he turned upside down during the years following World War II would never recover, and that's a debt we'll never be able to repay. ~ Bill Dahl, Rovi