In 1966, they signed with Bill Collins (father of Mojos bassist and future actor Lewis Collins) as manager, who moved the group to London and got them seen in clubs and other venues around the city, which helped to bring them to the attention of Ray Davies of the Kinks -- he expressed an interest in producing them, and got them signed to the same booking office, the Harold Davidson Agency, that handled the Kinks and the Small Faces. They auditioned successfully as the backing band for a singer named David Garrick, who had scored a hit with his recording of the Mick Jagger/Keith Richards song Lady Jane and was about to go on tour. Collins also pushed the bandmembers to start writing songs and develop their own material.

Late in 1967, Jenkins, who'd never taken to songwriting and seemed to be contributing ever less to the band, left the lineup and was replaced by Liverpool-born Tom Evans, from a Motown-inspired group called Them Calderstones. He proved to be not only a more than adequate successor as a guitarist, but a gifted composer as well. After surviving what could have been a devastating crash of its van in October of that year, the band picked up considerable career momentum going into 1968. Their gigs were well received and they were writing lots of songs, and in the course of working in their own studio, they'd also begun learning how to get their demo recordings to an extremely high level of sophistication, so that they sounded almost like finished commercial recordings -- and they now had songs good enough to open doors.

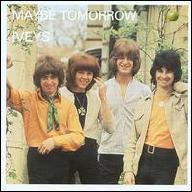

All of these elements -- the songwriting, the gigs, and the confidence -- came together when Collins arranged for an old friend, Beatles personal assistant Mal Evans, to come to a show at the Marquee Club on January 25, 1968, in the company of Peter Asher, the A&R head of the Beatles' new Apple label. Evans, in particular, was sold on the band and began bringing the group's demo recordings to Apple's offices, and by May of 1968 the Beatles were ready to sign the group, with a contract drawn up and executed in July. One of the demos that they submitted, Tom Evans' Maybe Tomorrow, became their debut single, released in November of 1968 -- for reasons that nobody could ever explain, it never charted in England and never made the American Top 40, stalling at number 67. Its failure in the face of anticipated success prompted a rethinking of the group's and the label's strategies -- they'd recorded a debut album, named after the single and utilizing more accomplished versions of some of the better (though not necessarily the best) songs they'd brought with them to the label, but it was shelved. Or, at least, it was supposed to be shelved.

Heard today, Maybe Tomorrow comes off as a pleasing if somewhat uneven amalgam of sounds, partly owing to the presence of two producers, Tony Visconti and Mal Evans, and also to the era in which it was recorded. See-Saw, Grandpa was a '50s-style rocker that also recalled the Beatles' Eight Days a Week in its guitar-flourish opening, while the lush, harmony-laden Beautiful and Blue might have passed for a Bee Gees effort during the latter group's five-man lineup period (Pete Ham even plays a bit like Vince Melouney here). The McCartney-esque ballad Dear Angie, written and sung by Griffiths, is followed by the harder, beat-driven Think About the Good Times, which could've been a low-key Kinks number circa The Kink Kontroversy. The pounding, RB-inspired Sali Bloo, the catchy pop/rock I'm in Love (which might have done well in the hands of the Bay City Rollers a few years hence), and the nostalgia-laden, '20s-style They're Knocking Down Our Home fill out all but the last slot on the original side two -- the latter song would have been unthinkable for a rock roll band to do, except in an era in which Paul McCartney had scored with When I'm Sixty-Four and You Mother Should Know, and in which the most recent albums by the Beatles and the Monkees included Honey Pie and Magnolia Simms, respectively. And the soaring I've Been Waiting finished the record with the Iveys throwing away song structure and elaborate production, stretching out and jamming in the studio.

It wasn't a bad album -- it was a little studio-bound, and one couldn't imagine the group playing some of this material on-stage, at least in the way it was presented here by producer Visconti, but the overall record commanded more than a couple of listens. Indeed, nearly 40 years later, it comes off very well as a collection of all-original songs by an untried band, and had it gotten a regular release, it just might have sold halfway decently at the time, especially propelled by Maybe Tomorrow's number five hit status in Germany and number one spot in Holland. Instead, the album more or less sneaked out, and ended up one of the rarest of Beatles-related vinyl artifacts, right up there with Paul McCartney and Richard Hewson's Thrillington album, commanding triple-digit prices on vinyl.

Possibly owing to the looseness of the Apple organization, or the hunger at EMI (Apple's distributor) to generate some hits with non-Beatles Apple product, Maybe Tomorrow managed to get issued, sort of -- some copies were distributed in England before it was pulled, while in Germany, Japan, and Italy, where the single had done well, the LP actually stayed in print for a short time. A follow-up single for those markets was also designated, in Ron Griffiths' punchy ballad Dear Angie. It was to be Griffiths' greatest moment of triumph and virtually his swansong with the band. During the summer of 1969, the Iveys were approached by Paul McCartney with the notion that they -- and not he, as he'd unwisely contracted to do -- would provide the songs to a movie called #The Magic Christian, starring Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr; for starters, however, they'd have to try to record the one song that McCartney had written for the project, called Come and Get It.

At first, they didn't realize what a gift they'd been handed -- having spent three years writing ever more (and better) original songs, the band didn't take kindly to covering someone else's material, or to mimicking the attributes of the demo that McCartney had brought with him; they didn't realize at first that they'd latched onto one of the last manifestations of extraordinary Beatles creative largesse, harking back to the days when their song bags were so full and their recording and concert commitments so demanding that McCartney could happily give A World Without Love to Peter Gordon, or John Lennon could take a hand in Billy J. Kramer's sessions and give the singer Bad to Me. McCartney's gesture in 1969 put the Iveys in rarefied company, right up there with his longtime friend Cilla Black.

The single -- with vocals by Tom Evans -- would become everything that they needed, reaching the Top Five in England and the Top Ten in America, and the band cut a handful more tracks of their own for the film soundtrack and the accompanying album. All of these activities coincided with a series of major career decisions, the most important of which concerned the continued participation of Ron Griffiths as a member -- now married and with a child to provide for, he had moved apart from the others socially, and lost his devotion to the music. When the smoke cleared from the #Magic Christian sessions, Griffiths was gone, to be replaced by veteran Liverpool-born guitarist/singer Joey Molland, who had lately come off of a stint with Gary Walker the Rain. Griffiths' exit also heralded their decision to switch to a new name: Badfinger.

The Iveys were consigned to history and even many of their better songs (ironically, Griffiths' Dear Angie among them) were reclaimed by Badfinger -- half a dozen of the tunes from Maybe Tomorrow ending up remixed and reissued on Badfinger's official debut album, Magic Christian Music. Ever since, the Iveys have usually been regarded as a subsidiary part of the ultimately tragic Badfinger story. In the opening years of the 21st century, however, there was reportedly found a huge trove of Iveys demos left behind in the Apple publishing archives, in which it is claimed there are songs as good as or better than the material chosen for Maybe Tomorrow; five of them were issued on RPM Records' 2003 compilation CD 94 Baker Street: The Pop-Psych Sounds of the Apple Era 1967-1969, which seem to bear out this claim. More and better releases from this body of music are promised, which would, in turn, seem to promise a major reassessment of the Iveys' significance. ~ Bruce Eder & Richie Unterberger, Rovi