While touring with Lloyd Price (Personality, Stagger Lee), Van Dyke met fellow Detroiter James Jamerson in Rockville, NY, in 1959. The phenomenal bassist was backing another Detroiter, singer Jackie Wilson (Reet Petite, To Be Loved, Lonely Teardrops, That's Why I Love You So). Jamerson had been recording for an upstart label called Motown Records headed by a young songwriter/producer named Berry Gordy. Gordy had written or co-written all of Wilson's hits to that point. Jamerson enthusiastically encouraged Van Dyke to move back to Detroit and become part of something that was going to be big. Van Dyke didn't decide to join Motown until 1962, with the help of a solid 150 dollars a week job offer from Mickey Stevenson of Motown's A&R department. Well, not exactly 150 dollars a week. Just after joining the label, Van Dyke's "pay" for a session was a bowl of soup. He also saw that he wasn't the only piano player on the block. There was Motown's first pianist Joe Hunter and pianist Johnny Griffith.

When Hunter left Motown in 1963, Stevenson named Van Dyke the bandleader for the Funk Brothers. Based around pianist Van Dyke, bassist Jamerson, and drummer Benny Benjamin, other key members were guitarists Robert White, Eddie Willis, and Joe Messina; percussionist Eddie Bongo Brown; vibist/percussionist Jack Ashford; and later, "replacement" drummers Uriel Jones and Richard Pistol Allen. Jones replaced an ailing Benjamin as the timekeeper on Gladys Knight and the Pips' I Heard It Through the Grapevine while Benjamin did the fills. The group's version of the song stayed at number one R&B for six weeks in December 1967 and went to number two pop. (Marvin Gaye's cover held the number one R&B spot for seven weeks in December 1968 and went to number one pop.) Once the march of the Motown hits began, Van Dyke and the rest of the band were on call 24 hours a day, every day of the week. All-day recording sessions became common with a few scant hours left to maintain family and personal relationships, relax, or keep their chops up by playing jazz at the Twenty Grand Club, Phelp's Lounge, and their favorite after-hours haunt, the Chit Chat Club. Sometimes their set would be interrupted by a Motown producer arriving and saying that they needed the band for a impromptu recording session and they'd reluctantly go to the recording studio to lay tracks in the pre-dawn hours. The band became so tight that the label would have them record rhythm tracks (no singers, not even an actual song) and would later add vocals to them after a song had been written to fit the tracks. In some instances, a band member would have a part that he created replaced and recreated by a vocal line or riff.

With Motown having hit after hit, you'd think that the pay scale of the Funk Brothers would've increased. But that wasn't the case, so Van Dyke started a musician's strike during a 1965 European tour when the band was asked to play backing tracks for Motown acts appearing on a British television show. Originally, they had been told that the acts were all going to lip-sync. After that incident, Van Dyke was looked on as a spiritual sage, big brother, and a parental figure by the rest of his fellow Motown studio musicians. This proved especially helpful to core rhythm section members Jamerson and Benjamin who were wrestling with growing substance abuse and health problems. In 1967, though Motown's prime songwriting/production team of Holland-Dozier-Holland left the label amid lawsuits and royalty disputes, internal riffs in the Temptations and the Supremes, Van Dyke and company were getting paid better than ever. Just that previous year, Van Dyke had made 100,000 dollars from Motown and his outside work. Also because of the emerging, wider-sounding eight- and 16-track audio tape recorders and mixing boards that Motown had purchased for its Hitsville recording studio, Van Dyke's piano could be heard, no longer (sonically) crammed into the label's previous three-track mixed releases.

Though the musicians were paid well for their services, they were still well below union scale. This being a commonly known fact in the Detroit music community, several music entrepreneurs, local and otherwise, took advantage of the situation and offered the band more money, leading to the Funk Brothers being heard on a lot of backdoor sessions. For the local Golden World and Ric-Tic label owned by Twenty Grand Club owner Ed Wingate, the band can be heard on Agent Double-O Soul by Edwin Starr (number eight R&B) and Stop Her on Sight (number nine R&B), I Just Wanna Testify by the Parliaments (number three R&B), and for Ollie McLaughlin's Karen label, Cool Jerk by the Capitols (Top Ten R&B, number seven pop). The band can be heard on records issued by the numerous labels that sprang up in lieu of Motown's phenomenal success.

Making the trips to nearby Chicago, they cut several hits for producer Carl Davis and Jackie Wilson: Whispers (Gettin Louder), recorded on August 8, 1966, and released September 1966, the song went to number five R&B and number 11 pop; Just Be Sincere; (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher, which set the stage for Wilson's mid-'60s comeback and was his second number one R&B single on October 7, 1967; Since You Showed Me How to Be Happy; I Get the Sweetest Feeling (later covered by B.J. Thomas) cruised to number 12 R&B in June 1968; and (I Can Feel Those Vibrations) This Love Is Real went to number nine R&B in November 1970. The success of these records, both commercially and aesthetically, suggest that if Wilson had been signed to Motown, he would have had a more consistent career. It's even more ironic given that Gordy's first big break came as one of Wilson's early songwriters in the late '50s. Another big hit featuring the Funk Brothers was Then Came You by Dionne Warwick and the Spinners (Top Ten R&B, number one pop, October 26, 1974). As far as Warwick was concerned, this was a continuation of a long collaboration. During the '60s, Warwick's songwriting/producing duo, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, would have clandestine rendezvous with the Funk Brothers at Detroit-area recording studios. The band also traveled south to record in Muscle Shoals and Atlanta, among other cities. With This Ring by the Platters also featured the band.

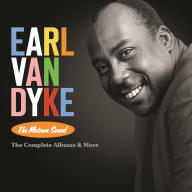

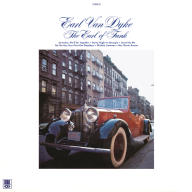

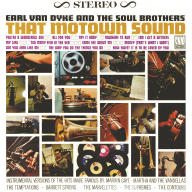

1969 was the year that some issues came to a head. After years of chronic health problems and a heroin addiction, Benny Benjamin died and James Jamerson's alcoholism began to take its toll. The musicians began to bicker with the label about their pay scale and their lack of name recognition (the musicians were never listed on the back of the album jackets). Also that year, after years of rampant rumors, Motown Records relocated to Los Angeles, partly based on Berry Gordy's desire to become involved in the motion picture business. The company did have two cinematic successes, the box office hit #The Lady Sings the Blues, starring Diana Ross, Billy Dee Williams, and Richard Pryor, and the charming tribute to Negro League Baseball, #Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings starring Williams, Pryor, and James Earl Jones. Motown made it known, if not by words but certainly by action, that they wanted Van Dyke and company to remain in the recording studio, laying the foundation for the label's many hits. But the Funk Brothers long wanted to release an album of their own and somewhat got their wish granted, with Earl Van Dyke Plays the Motown Sound and The Earl of Funk (September 1970), both released on Motown's subsidiary label Soul. Neither release was what they really wanted, though, which was a straight-ahead jazz album. On Plays the Motown Sound, Van Dyke played organ lines over existing Motown tracks. Motown objected to the word "funk," so both releases carried the moniker Earl Van Dyke and the Soul Brothers.

During 1970, Van Dyke began to accompany mainstream lounge acts when they would appear in the Detroit area and began working with Freda Payne as her musical director. Van Dyke joined the in-house band at the Hyatt Regency in Dearborn, MI, backing singers Sammy Davis, Jr., Vic Damone, Mel Tormé, and others when they came thorough town. Motown would still send tracks back to Detroit for the few remaining Funk Brothers to add overdubs for several years after their departure. Jamerson and Van Dyke moved to California separately at different times during the '70s. Though a couple of years later in the mid-'80s, Van Dyke moved back to Detroit after not being able to adjust to the California lifestyle. He got a job with the Detroit Board of Education at Osborne High School. Van Dyke still gigged locally and did advertising jingle recording sessions, the occasional record dates (the Four Tops' Catfish [ABC Records, October 1976] and The Show Must Go [ABC Records, October 1977] albums), local festivals, the Jimmy Wilkins band, and his own ensembles. 1991 was the year that marked the end of Van Dyke's playing days as he succumbed to the debilitating carpal tunnel syndrome. The following year in September of 1992, at the age of 62, Van Dyke died of prostate cancer at Harper Hospital in Detroit. His funeral services were held at St. Anthony Catholic church. With the deaths of Benjamin in 1969, Jamerson in 1983, and Van Dyke in 1992, the end of an amazing era in pop music was sealed. ~ Ed Hogan, Rovi