The son of a dentist, Ormandy's father wanted him to be a violinist, and he began his musical training at age two. He was already capable of recognizing serious musical works at that age, and when he was five he entered the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest. He had his master's degree at age 14, and received an artist's diploma at age 16 as a violinist, at which time he also received a degree in philosophy from Budapest University. He toured as a violin prodigy just before the outbreak of World War I and remained a Hungarian national during the war, becoming a professor at the Hungarian State Conservatory when he was 20 years old.

Ormandy came to conducting completely by accident. In 1920, he came to America based on a promised series of violin concerts that never materialized, and during his stay, he joined the orchestra of the Capitol Theater in New York City. He quickly moved up the position of concertmaster, and some eight months later, when the theater orchestra's conductor suddenly fell ill, Ormandy was asked to fill in for him at the podium. He was appointed the orchestra's conductor, a post that he ended up holding for seven years, giving as many as 20 performances a week. This experience enabled him to develop an effective technique of communicating with his players and coaxing exceptionally polished work from his musicians.

Ormandy was good enough that, at the end of 1927, he became the conductor of the CBS Radio Orchestra. This was a prominent broadcast orchestra, while the accompanying reduction in the number of performances he had to give each week afforded Ormandy the chance to see conductors such as Wilhelm Furtwangler, Willem Mengelberg, and Arturo Toscanini working with the New York Philharmonic. Toscanini was the most important influence on his own technique with an orchestra during his early, formative years, although later on he was more heavily influenced by the musicianship of Otto Klemperer. In 1930, Ormandy was offered the chance to conduct the New York Philharmonic in a series of outdoor concerts at Lewisohn Stadium. A year later, he was chosen to substitute for Toscanini conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the success of those concerts resulted in his being appointed as head of the Minneapolis Symphony in 1931. Ormandy's Minneapolis appointment gave him an opportunity to choose programming of his own, and among the groundbreaking works that he brought into the repertory was Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 2, a massive work for orchestra, chorus, and soloists, which was later preserved in a live recording at Northrup Auditorium, the first American recording of a Mahler symphony and the first electrical recording of this symphony. It was also with the Minneapolis that Ormandy acquired his first experience with the recording process -- the orchestra was heavily recorded by RCA in the mid-'30s in long sessions over many weeks, ultimately setting down over 100 works, including the Mahler Second. The experience he gained during these sessions served him well in his subsequent career, when many older conductors still regarded the recording process as not much more than a necessary evil.

By this time, he was beginning to develop a reputation in Europe, and in 1936 Ormandy conducted at the Bruckner Festival in Linz, Austria. Ormandy was appointed co-conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in the mid-'30s, sharing the job with Leopold Stokowski, and when Stokowski resigned his position in 1938, Ormandy was made music director. He held the music directorship there for more than 40 years, and although he occasionally accepted guest conductor engagements, it was with the Philadelphia Orchestra that Ormandy was most closely associated for the next four decades. He also enjoyed warm and cordial relations with the members of the orchestra, in contrast to his somewhat more strained and formal contact with the Minneapolis Symphony. On the negative side, Ormandy was uncomfortable with women in the orchestra, and it was relatively late that Philadelphia took on its first female violinist, supposedly when he auditioned one woman player who was so good that he couldn't turn her down.

During this period, from the '40s to the '70s, Ormandy solidified the Philadelphia Orchestra's reputation as the most "artistocratic" of major American orchestras. Stokowski, who understood recording technology better and earlier than almost any other conductor, had already established its reputation somewhat on early 78 rpm recordings, but it was Ormandy who further polished the Philadelphia's sound and reaped most of the rewards, with the advent of the long-playing record and, later, stereophonic (and, briefly, quadrophonic) sound. He recognized that, apart from the source of income that recordings (especially LPs) could represent, they were the best "advertisement" that an orchestra and conductor could have, in terms of establishing a reputation far beyond their home city and its audience. He was also well aware of the advantages that his Columbia Masterworks rivals the New York Philharmonic had, in terms of being in the media capital of the world, and he did his best to make the Philadelphia Orchestra fully competitive with both. Ormandy was doubly shrewd in his programming, seeing to it that recording and concert schedules meshed, to keep the amount of rehearsal time to a minimum and maximize the amount of useful time spent in the studio.

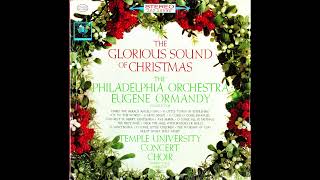

The result was a massive number of recordings over the next 40 years, most of them smoothly polished and seamless, and extremely popular, especially with the advent of the long-playing record and stereo record. He began with RCA, but in 1943, Ormandy and the Philadelphia signed a contract with Columbia Masterworks that was to last 25 years, until 1968, and resulted in a massive number of recordings.

His interests ranged fairly far and wide. Ormandy conducted and recorded some Mozart and Haydn, and Bach and Handel weren't totally outside of his repertory (his Columbia recording of Messiah was extremely popular, though it was also heavily cut and inauthentic in ways that would drive modern critics and audiences to distraction), and he could conduct a serviceable, even inspired Beethoven symphony; he made several first recordings of works by Anton Webern, and helped popularize the works of Samuel Barber and Charles Ives; late in his career, he even tackled Penderecki's work, and his recording of Paul Hindemith's Mathis der Maler symphony may be the best in the catalog. But it was for the romantic pieces -- by Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, Dvorak, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Smetana, Liszt, Richard Strauss, et al. -- what today are called the "warhorses," that he was best-known and most well-liked.

He also extended his repertory occasionally into new and unexpected areas. When Deryck Cooke prepared a performing edition of Gustav Mahler's unfinished Symphony No. 10 in the early '60s, it took years for this addition to the composer's oeuvre to be accepted even by many younger first-ranked conductors, and many established figures, including Leonard Bernstein, never accepted or conducted the realized Tenth. Ormandy not only accepted the work and conducted it in concert, but recorded it, in one of the Philadelphia's few notable recordings of Mahler's music. Similarly, Ormandy recorded the so-called Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 7. During the mid-'60s, he also recorded an unexpectedly good collection of music by Frederick Delius, a composer whose music had always been considered to be exclusively the province of English conductors.

Some of these decisions were purely practical -- even in the '60s, there was a repertory squeeze afflicting the classical recording industry, with too many conductors doing too few major pieces by the major composers; by being the first to record either the Mahler or the Tchaikovsky, and other works like them, Ormandy saw to the Philadelphia's reputation and its income by moving beyond the repertory of his competitors.

Ormandy began recording in the mid-'30s with the Minneapolis Symphony, including Schoenberg's Transfigured Night and Griffes' Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan, but apart from his early recordings of Mahler's Symphony No. 2 and Bruckner's Symphony No. 7, most of these are solely of historical interest. Ironically, his later recordings of Mahler and Bruckner, apart from Mahler's Tenth, were less important, although his Bruckner recordings may have helped spread the reputation of the composer at a time when few American conductors, orchestras, or record labels were willing to risk very much behind Bruckner's symphonies. His notable early recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra include the Brahms Alto Rhapsody, with Marian Anderson as the soloist, Samuel Barber's Essay for Orchestra No. 1, and Hart McDonald's Symphony No. 1.

Ormandy's recordings were especially popular during the '50s and early '60s, when the phenomenon of stereo drew many audiophiles into the realm of classical music. The orchestra's polished sound was precisely what these listeners, who unknowingly paid many of the expenses behind more serious but less profitable recordings, were looking for. Ormandy's smooth approach to music, even modifying scores at will to make them sound "better," made him a good choice with the Philadelphia to provide accompaniment on numerous concerto recordings, most notably the Sibelius Violin Concerto, with David Oistrakh as soloist.

Later on, as the classical audience became more stratified and more sophisticated, his popularity among critics and record buyers slipped, as they began to note a lack of depth in his work. He maintained a following among older listeners in the late '60s, however. He and the Philadelphia Orchestra returned to RCA in 1968, after an absence of 25 years, and began re-recording much of his most popular (if not always best) repertory, previously done for Columbia, yet again. More than ten years after moving back to RCA, Ormandy and his orchestra became pioneers in the then-new digital recording process, recording one of the label's earliest digital releases. By then his interpretive instincts were beginning to waver, and even longtime supporters had to acknowledge that Ormandy's time was drawing to a close.

Ironically, Ormandy's success with the Philadelphia Orchestra has come to haunt the orchestra in the years since. Philadelphia was subsequently led by Riccardo Muti, and more recently by Wolfgang Sawallisch, and in Sawallisch's case, they continue to get an enthusiastic response from critics. But the recordings they did with Ormandy during the stereo era on Columbia, in particular, continue to sell well, and have eclipsed many of their more recent efforts, despite high praise heaped upon the Sawallisch-era recordings. Sony Classical (Columbia's successor) has continued to reissue ever more of their Ormandy performances, even as EMI in 1997 dropped the current Philadelphia Orchestra over lackluster sales. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi